Finetuning Approaches

Finetuning in terms of generative models means the general concept taking a pre-trained, “foundational” model and updating its parameters using new data. This data is usually much smaller than the data used to train the original model. The goal is to adapt the model to the new data while preserving as much of the knowledge it has already learned from the original training data. We have already seen an example of a finetuning approach when we were talking about instruct-tuned models Instruct-tuned models. These models are based on plain MLM-trained language models, that are then trained on new data that is presented in a Instruct - Response format. The result of this specific example of finetuning was a model that, instead of just completing a text, answered in the format present in the finetuning data.

Though the central concept of finetuning is always the same, i.e., updating the parameters of a pre-trained model using new data, there are many different ways to do this. The following sections will give an overview of some of the most common approaches.

Full Finetuning

Full finetuning is the simplest approach to finetuning. As the name says, it is based on completely updating the parameters of the pre-trained model using new data. This means that all weights of the model are updated during training using regular gradient descent or a variant thereof. The main advantage of this approach is that it is very simple and easy to implement. Complete (few-shot) fine-tuning has also shown to perform better in the domain of finetuning and in Out-of-domain tasks when compared to Few-Shot-Prompt-approaches (Mosbach et al., 2023). However, it also has some disadvantages.

Firstly, it can be computationally expensive as it requires training all parameters of the model.

Secondly, it can lead to catastrophic forgetting, i.e., the model forgets what it has learned during pre-training when adapting to new data (Luo et al., 2024).

Parameter-Efficient Finetuning (PEFT)

Another approach to finetuning is to not update all a models parameters but to (partially) freeze them and only update a small subset of the parameters or to train an adaptor module that can be added to the model. This approach is called parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT). The main advantage of PEFT is that it is much more computationally efficient than full finetuning as it only requires updating a small subset of the parameters. We will look at three different approaches to PEFT:

Prompt-based Finetuning (Prefix-tuning and Prompt tuning)

- Bonus: TextGrad

Adapter-based finetuning (Low-Rank Adaptation and its relatives)

(IA)³ (Infused Adapter by Inhibiting and Amplifying Inner Activations)

Prompt-based Finetuning

Prompt-based finetuning is a family of methods that use so called “soft-prompts” to guide a models generation. The general concept is pretty close to prompting as we discussed it in Prompting. The main difference is that instead of engineering a prompt constructed from discrete tokens that results in opportune results, we let standard optimization procedures find a continuos embedding-vector in a pre-trained LMs embedding-space. Prefix-Tuning, Prompt Tuning and P-tuning are three different approaches to prompt-based finetuning - all utilizing some implementation of this soft-prompt concept.

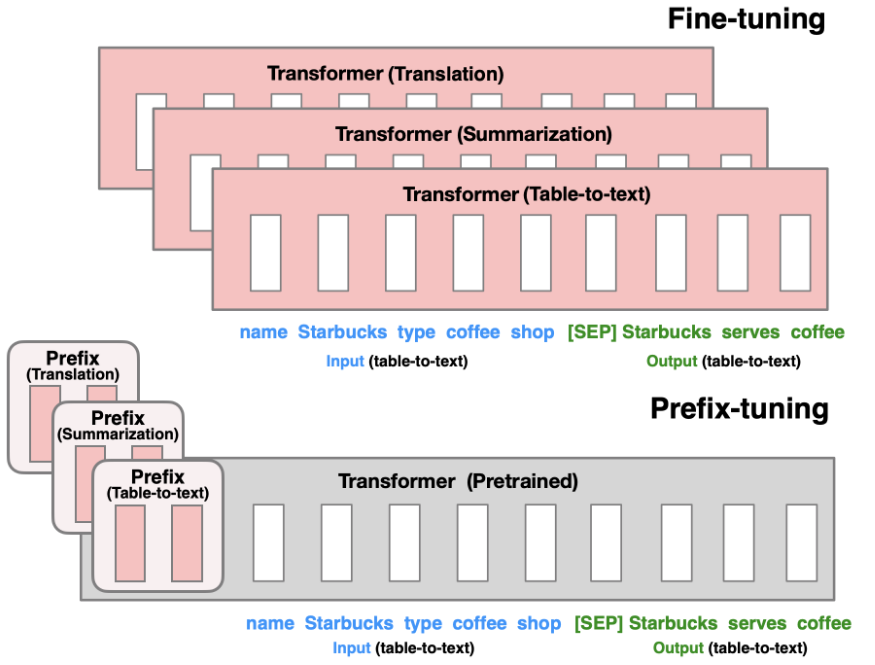

Prefix tuning

Prefix-Tuning (Li & Liang, 2021) is a method of adapting a language model to a specific down-stream task by adding a continuous prefix vector to the input embeddings. This is done by learning a continuos matrix with a set amount of columns (i.e., tokens) and the frozen models embeddings-dimensionality1 that is prepended to the input of each transformer layer (i.e., the encoder and the decoder-stack). The principle is illustrated in Figure 13.1.

1 Since directly learning the prefix-weights proved to result in unstable performance, the authors did not directly train prefix-vectors but a MLP scaling up from a smaller dimensionality to the embedding size. Since the rest of the proxy-model is discarded after training though, the method can be treated as the same principle.

This vector can then be used to guide the model during inference. The main advantages of this method are

- a small number of parameters that need to be learned and

- the ability to quickly adapt to different tasks by simply switching out the prefix vector.

Since the learned prefix-weights have to be prepended to each input though, one has to have access to the models internal representation during inference (at least for encoder-decoder-stacks). This is not always possible, especially when using black-box models like LLMs that are hosted on a remote server.

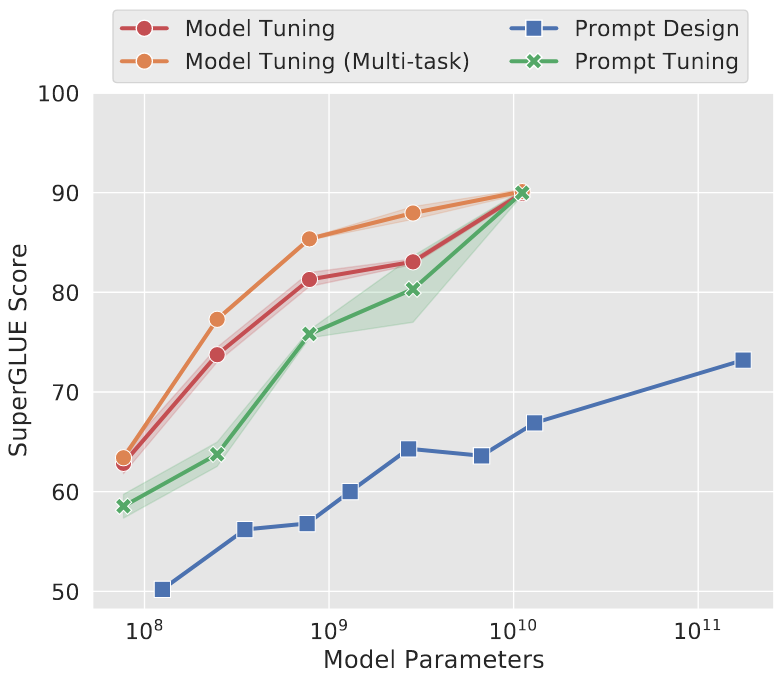

Prompt-Tuning

Prompt-tuning (Lester et al., 2021) is a method that is conceptually very similar to prefix-tuning, but avoids the need for accessing the internal representation of the model during inference by using what the authors call “soft prompts”. Again, instead of prompting using discrete tokens, continuous “special tokens” are learned that are concatenated to the input embeddings. The main contribution of Prompt-Tuning over Prefix-Tuning is a) that they showed that inputting the soft-prompts to the encoder alone suffices and more importantly b) that the performance of models fine-tuned in this manner is comparable to full finetuning, at least for larger LLMs (Figure 13.2).

Your turn!

The huggingface-page on prompt-based finetuning describes three more variants of soft-prompt finetuning:

Select one of the three and try to answer the following questions in a markdown-file:

- What is the core principle?

- What is the context in which this tuning method is most efficient?

- How much memory can be saved by leveraging this technique (if you can find this indication)

Present your results to the group. Upload your results to moodle.

TextGrad

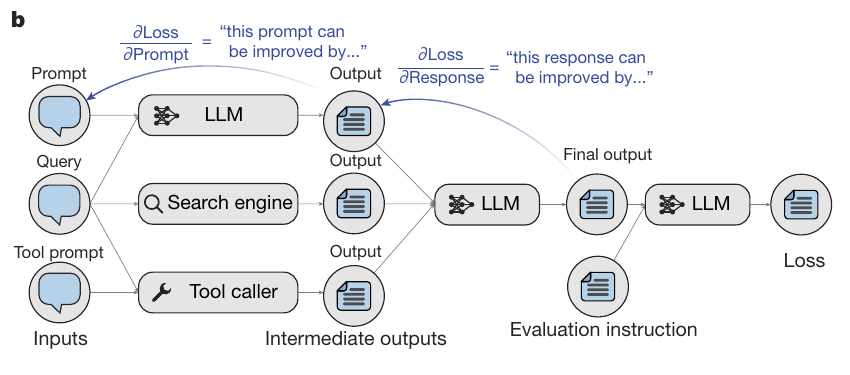

Yuksekgonul et al. (2025) described a method for text-based auto differentiation. The authors claim that, given a loss-target, their approach “TextGrad” allows to improve a model’s performance by directly tuning the discrete textual prompt used for generating the model’s answer across various tasks. This is done by implementing a system analogous to the autograd implementation in PyTorch (see Figure 13.3 for an illustration).

A “loss”-function is defined, i.e., any function that takes the textual output and evaluates its quality. This can be a classic loss function like binary accuracy or a set of rules for evaluating text quality that are given to a language model to compare the result with the ground truth. This “loss” is then taken into account by the “optimizer”, which is another LLM-Call that takes the output and loss and critiques the appropriate Variables (i.e., the initial prompt). This critique or “gradient” as it is called in the Autograd analogy is then taken to update the initial prompt using another LLM-call (the step in Autograd). This process continues iteratively until the results are satisfactory or a predefined number of iterations is reached.

Your turn!

Install TextGrad and get the tutorial on optimizing a solution to run using the following snippet to initialize your LMStudio/Ollama server:

import textgrad as tg

from openai import OpenAI

from textgrad.engine.local_model_openai_api import ChatExternalClient

client = OpenAI(base_url="<your endpoint>", api_key="<some key>")

engine = ChatExternalClient(client=client, model_string="<your model of choice>")

tg.set_backward_engine(engine, override=True)If this tutorial runs for you, adapt the code so that it generates the reasoning to the following riddle:

A farmer with a wolf, a goat, and a cabbage must cross a river by boat. The boat can carry only the farmer and a single item. If left unattended together, the wolf would eat the goat, or the goat would eat the cabbage. How can they cross the river without anything being eaten? - Taken from wikipedia

Solution: goat -> empty -> wolf -> goat -> cabbage -> empty -> goat

Adapter-based finetuning

Instead of focusing on the embeddings and thus the input of the language models, LoRA and its relatives focus on adapting the output of the attention and feed-forward layers of a transformer. The family of Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) methods (Hu et al., 2021) we will discuss here is a group of parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques that adapt the models output by injecting trainable rank decomposition matrices into a transformers layer, greatly reducing the amount of parameters that need to be learned.

LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation)

The first and most common candidate of the group of LoRA-finetuning techniques is the name giver itself: Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). Hu et al. (2021) criticized soft-prompting methods as being hard to optimize2 and being dependent on reserving part of the input space for the prompt, effectively reducing the context window.

2 As was also reported in Li & Liang (2021) in the context of their reported unstable learning.

LoRA builds on the findings by Aghajanyan et al. (2020) that the intrinsic dimensionality of transformer layers is low, i.e., that there exists a lower dimensionality representation of the models parameters that suffices for an effective finetuning and thus only a few parameters are needed to adapt them. They show this by successfully finetuning a model on a random projection to a far smaller subspace without losing too much performance.

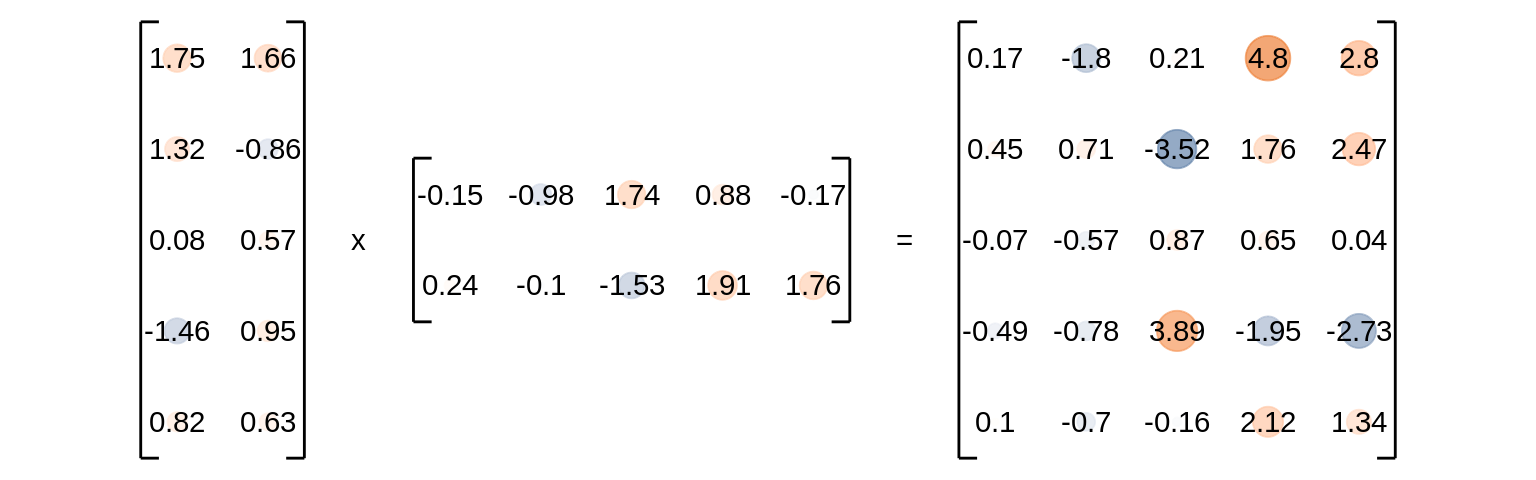

The central idea behind LoRA is that finetuning can be represented as learning the updates to the models parameter matrix \(\Delta W\) so that the results of a fine-tuned generation \(h\) is based on the initial weights \(W_0\) and the update \(\Delta W\):

\[ h = W_0x + \Delta Wx \]

Based on the idea of Aghajanyan et al. (2020), LoRA approximates this update matrix as the product of the lower-rank matrices \(A\) and \(B\), where \(B \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{in} \times r}\), \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times d_{out}}\) and \(r << d_{in}, d_{out}\):

\[ h = W_0x + \Delta Wx = W_0x + BAx \]

A is initialized with random values sampled from a normal distribution and B is initialized as a zero matrix so that \(\Delta W\) is zero at the start of the training.

This results in a reduction of the number of parameters to be trained from \(d_{in} \cdot d_{out}\) to \(d_{in} \cdot r + d_{out} \cdot r\) as is illustrated in Figure 13.4.

QLoRA (Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation)

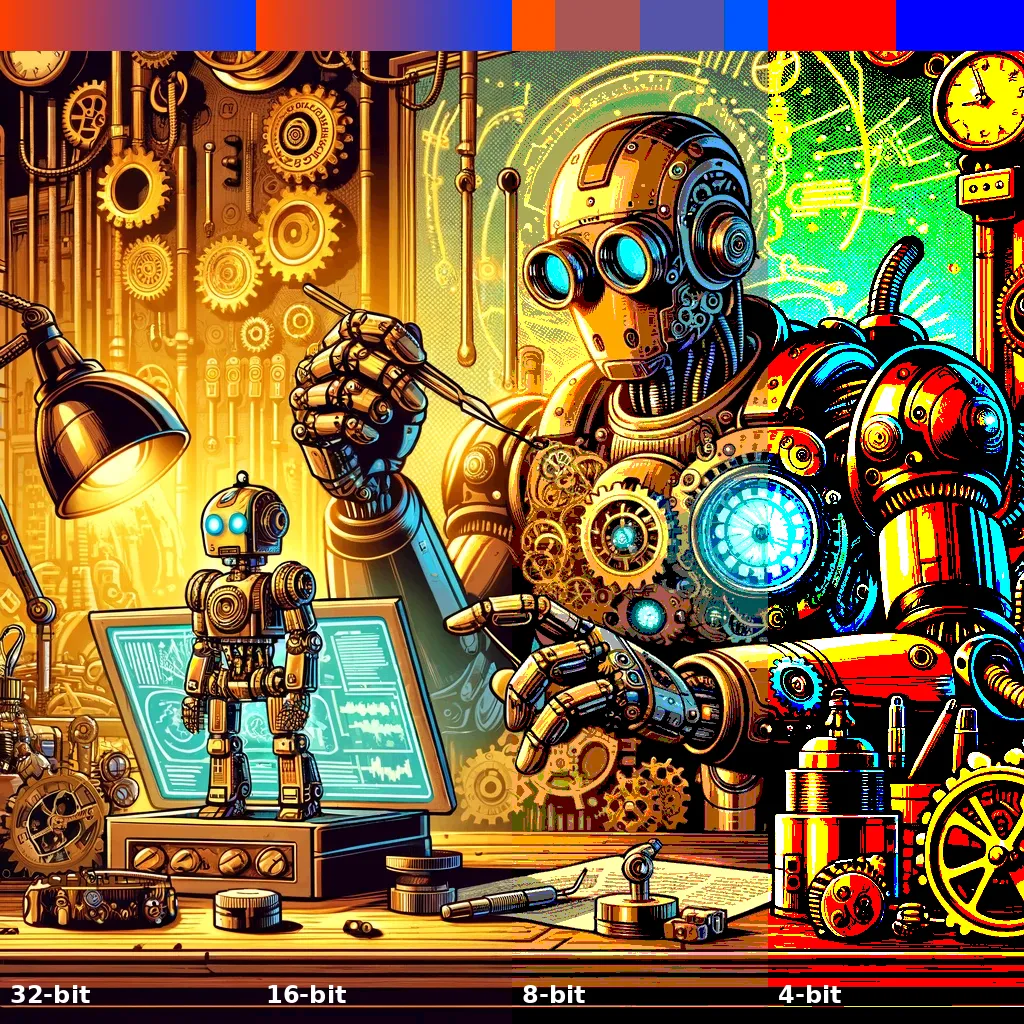

QLoRA (Dettmers et al., 2023) builds on the concept of LoRA by further reducing the memory footprint and computational requirements. It does this, next do some other optimizations, by quantizing, i.e. reducing the precision of, the frozen pretrained LLM. The process of quantization is illustrated in Figure 13.5.

They report a reduction of GPU-requirements for finetuning a 65B parameter model from more than 780GB VRAM to a measly number under 48 GB, allowing it to be finetuned in a single GPU. They also report performance values of up to 99.3% of the performance of ChatGPT on the vicuna benchmark3.

3 which is now defunct and replaced by the MT-Bench score Chatbot Arena Leaderboard Week 8 (n.d.)

X-LoRA (Mixture of Experts with LoRA)

Mixture of experts is a pretty old idea generally (Jacobs et al., 1991) and has been used in the context of Deep Learning and more specifically NLP for quite some time now (Shazeer et al., 2017). There are also some examples for recent LLMs that are utilizing the concept to achieve better performance, e.g. Jiang et al. (2024) The basic idea is to split a model into multiple smaller models, each of which is an expert on a specific topic. During inference, the input is routed to the expert that is most likely to be able to answer the question. This can be done by having a router-model that predicts the topic of the input and then routes it to the corresponding expert. This approach was applied to LoRA-based finetuning by Buehler & Buehler (2024) who propose X-LoRA, which is a mixture of experts that uses LoRA-finetuned models as experts. This is done by training a set of low rank adaptation matrices and using a router-model that predicts a scaling factor for each expert based on the input. The output of the model is then the weighted sum of the outputs of all experts. This scaling is done on a token-by-token basis, which allows a highly granular control over the output of the model.

Unsloth

Unsloth (Daniel Han & team, 2023) is a python-module that implements LoRA-finetuning in a very efficient way that further reduces raining resource requirements. This is mostly done by a far more efficient Gradient Descent algorithm that is specifically optimized for LoRA finetuning (“Introducing Unsloth,” n.d.).

They additionally introduced dynamic quantization to their models, which allows them to further reduce the memory footprint without losing too much performance.

(IA)³

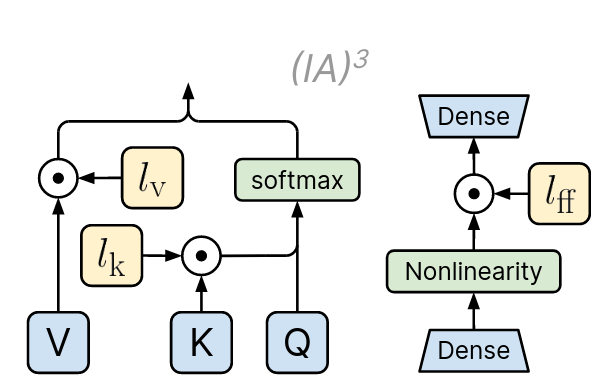

Liu et al. (2022) propose (IA)³ (Infused Adapter by Inhibiting and Amplifying Inner Activations) which additionally builds on the central concepts of Soft Prompting and LoRA. Instead of learning additional tokens to prepend to the input or adaptation matrices for each layer, they propose the training of a small set of additional vectors that are used to item-wise rescale select hidden states of the model. A schematic illustration can be seen in Figure 13.6.

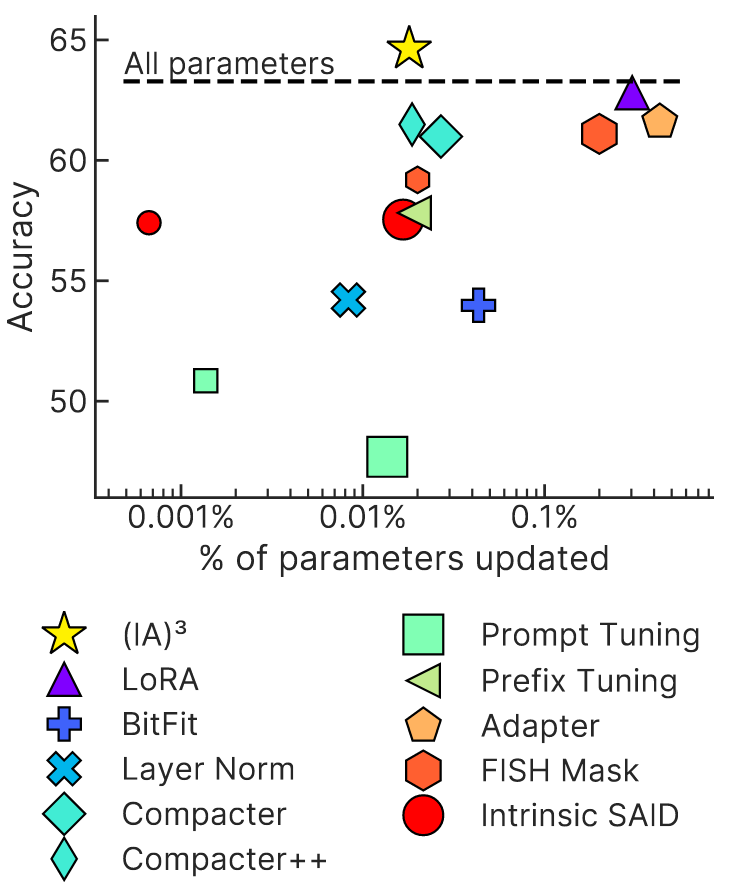

They also report their adaptation-strategy to work better and in a less resource-intensive way than LoRA and the other methods we have discussed so far, achieving higher accuracy with fewer parameters on their benchmark (Figure 13.7).

Additionally, they report a super-human performance of 75.8% on the RAFT, which provides only 50 training examples per task.

Further Readings

The huggingface-hub for PEFT-Methods is a great source to get an overview and a better hub to get to the original papers proposing the presented methods.

They also have a nice blogpost about MoE-models.